Ascending to Knowledge in the Eternal Present

A Companion to Collecting Contemporary Neoclassical Art

“There comes a time in life when you know what you like, and have to make up your mind to like what you know.”

VINCENT PRICE

PRAXIS

I know what I like: Classical Art.

Enthusiastically, the purpose of this quarterly journal, “PRAXIS” will be to share my understanding of the sensibilities present in contemporary Neoclassical Art with my fellow collectors.

*

Each of us embarking on this journey, whether novices or connoisseurs, will begin to discover what we expect from Contemporary Neoclassical art, what lessons we can learn from these artists about our complex society, and how our leisure time can be enriched while liking, and learning, a little more about the art we know.

(Journal note: All images: public domain-certifier, fair use, or by permission)

THE PURE PRESENT

Volume 1 Number 1

(Compiled from “Decline of the West” by Oswald SPENGLER, and other sources)

In Classical Culture all experience, not merely the personal but the common past, was transmuted immediately into a timeless, immobile, mythically fashioned background for the momentary Pure Present.

Memory, as such, became something different, since past and future are absent. The state of the Pure Present, to quote philosopher Henri Bergson, “is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future.” “In truth”, to quote Bergson further, “All sensation is already memory”. The Pure Present is timeless and changeless, polar not periodic, and frankly the stuff that Myth is made of.

Experiencing sensation in this manner gave the Hellenic “soul” an intensity that to us ‘moderns’, would seem to be almost unknowable. The sense of time (past/future) and the dictates of distance (periodic) are so ingrained in us now, that it would be very difficult indeed for us to merge a sentiment or an event into a timeless and immobile Pure Present.

Classical sculptors such as POLYKLEITOS, and writers like THUCYDIDES, made no distinction between things as they are and what they became, between story and document, between the periodic time element and its absence, the timeless. The Hellene accepted this circumstance. Everything about his culture, the small, the easy and the simple was comprehensible in one glance. Simplicity with majesty. No experts required.

It would be disingenuous of me to suggest that we can understand the message and sensibility of the Classical artists and writers with the same intensity as the Hellene. No substitution of Classical equivalencies, Spengler observes, will give you a Classical “soul”. “The soul” he observes, “Is the compliment of its extension…the direct expression of a certain type of humanity.”

However, given that Life can become the process of effecting human potential, it may be possible to appreciate the Classical sensations and sensibilities present in the work of Contemporary Neoclassical artists by transcending the prejudices of our thoroughly modern senses, and using criteria that approximates the Pure Present.

A basic litmus test follows.

- The Contemporary Neoclassical Artist (‘the CNA’) should have the power to bring alive and make self explanatory the sentiments and events of the modern world as he/she experiences it.

- The CNA should have portrayed the life and development of his or her figures in a manner that shows “the thing becoming” rather than “the thing become”.

- The images of these figures should be impressed from a living and developing world in motion, showing evidence of observation and comparison.

- The figures should be presented with immediate and inward certainty, treated with sympathy regardless of the circumstance depicted, and in a manner that exhibits at least some intellectual flair.

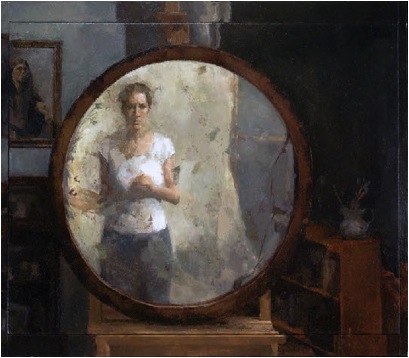

- Each image should reflect the true sensibilities of the CNA, almost as if he or she were holding up a mirror to their “soul”. True mind begotten forms…no pickings and stealings!!!

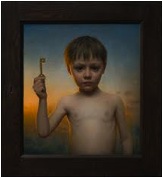

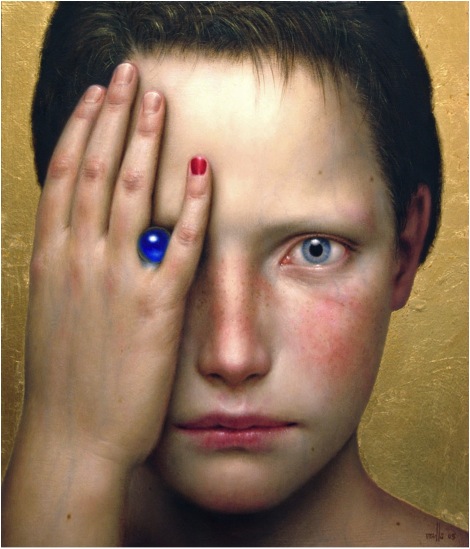

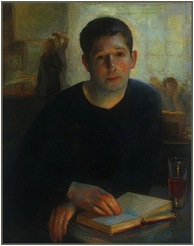

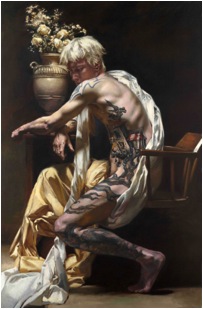

CONOR WALTON- “The Key”

And what should we, the viewers and witnesses to the sensibilities present in Contemporary Neoclassical Art, bring to our appreciation of the images offered to us?

At the very least, a modern APOLLONIAN soul, receptive to a Pure Present.

Again, a basic litmus test.

- The modern Apollonian will want to understand the significance of his/her being, and will look to Art for answers.

- He/she will appreciate that art is organic, both a language and a stock of forms, that will help the Apollonian reach out to the world around. “Imitation is born of the secret rhythm of all things cosmic” (Spengler)

- The Apollonian will recognize that the artist has not chosen his/her time, and that the importance and test of value for any given work, rests with the artist’s ability to see Destiny clearly.

- The Apollonian will shun art that has become a sport (art for art’s sake), one to be played out for a select group of connoisseurs and buyers, by artists who say what would have been meritorious to omit, and omit what is essential to say.

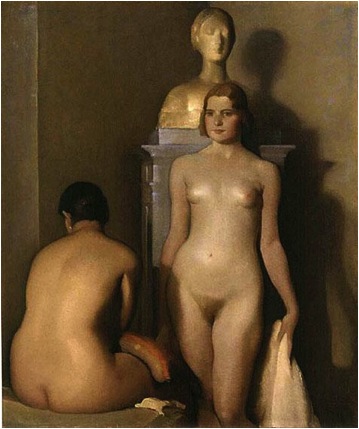

- He/she will have an unreserved acceptance of the sensuous instant; for example, knowing that the nude body is a self contained unit of being, not a Dionysian vessel of carnal overload. The Apollonian thus will appreciate the deeper meaning of the study of the nude, and the importance of the motif. He/she will be able to differentiate between clever, fleshly genre work and the representation of a life symbol.

- Further suggestions?? Let me know.

Jeremy LIPKING

(Journal

Note: A lot of the foregoing is contained in Oswald Spengler’s book, “The Decline of the West”. Published in 1918 (now in public domain), it is a dense, complex overview of the differences between Culture and Civilization. Amazingly prescient for its time, it offers a different world view of history, mathematics, art and religion from what we are used to. Not the easiest ‘read’, but ultimately rewarding for would be Apollinians (sic).

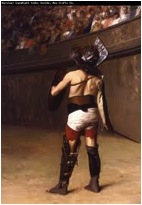

J L GEROME “Gladiator” (detail)

PANEM ET CIRSENSES

(One more Spenglerism)

“What is practised as art today is impotence and falsehood. Look where one will, can one find the great personalities that would justify the claim that there is still an art of determinate necessity? Look where one will, can one find the self evidently necessary task that awaits such an artist? We go through all the exhibitions, the concerts, the theatres, and find only industrious cobblers and noisy fools, who delight to produce something for the market, something that will “catch on” with a public for whom art and music and drama have long ceased to be spiritual necessities.”

CLASSICAL WHO’S WHO

Polykleitos and the Perfect 10.

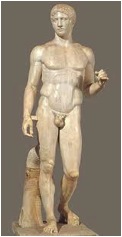

Polykeitos was an innovative Greek sculptor of the 5th Century BC, who used a numerical scheme to unify, rather than delineate, bodily proportion. Called ‘The Canon” (i.e. the rule or example) it is both a theory, and a statue.

The theory espoused a Pythagorian emphasis on number, proportion, commensurability, exactness, and beauty.

- Perfection comes about little by little through many numbers

- The numbers must all come to a congruence through some system of commensurability and harmony

- Perfection is the exact Mean in each particular case

- The perfect human body should be neither too tall not too short…but exactly well proportioned

- Such perfection in proportion comes about via an exact commensurability of all the body’s parts to one another

- Perfection requires scrupulous attention to replicating the body’s anatomy

- In bronze work such precision is most difficult when the clay is at the nail

Further reading : McHAGUE, Hugh- “Pythagoreans and Sculpture: The Canon of Polykleitos”

POLYKLEITOS- “THE DORYPHOROS”

The statue, known as ‘Doryphoros, or the Spear Bearer, approaches the Ideal figure in the Pure Present, by using a harmony of opposites. Depicted in contraposto, a posture in which the weight is placed on one leg, ‘Doryphoros’ shows a dynamic counterbalance between relaxed and tense body parts, and the direction in which they move (chiastic balance). The left or straight side (arm/leg) contrasts with the right or curved side (again arm/leg). The contrasts are further balanced by considering active (left) and passive (right)-chest (right), head (left); lowered/raised shoulders and hips.

It is sculptural fitness and rightness produced by ratios/numbers, or as Polykleitos said “… the employment of a great many numbers would almost engender perfection in sculpture”.

For modern Neoclassicists, the true value of both the theory and statue, however, lies in the word “almost”. It crystallizes the concept of ‘classic restraint’ we appreciate most in Greek sculpture.

“By using a complex series of simple ratios, it is possible to build up the coherent structure of an ideal figure…but each of these measurements must be tempered (by the truth) of natural appearances. It is in these little modifications of the canonic norm that the secret of bodily beauty is hidden”. (CARPENTER- “The Esthetic Basis of Greek Art”)

“Little modifications” made- “when the clay is at the nail”

Further reading: CARPENTER, Rhys- “The Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” and “Greek Sculpture”

THE PURE PRESENT OF SABIN HOWARD

“The history of the Classical shaping art is one untiring effort to accomplish a single ideal-the conquest of the free standing body as the vessel of the pure real present” (Spengler)

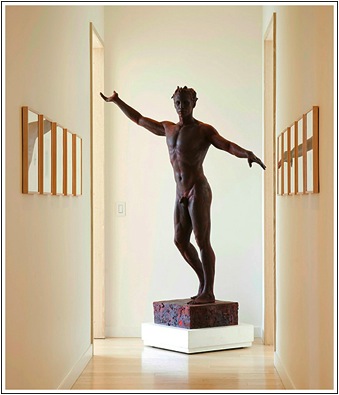

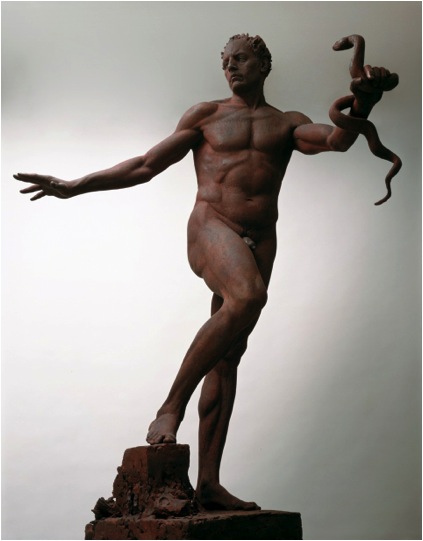

SABIN HOWARD “APOLLO” (in situ)

The arts in Classical culture begin with renunciation.

Greek sculptors in the 5th century BC renounced naive imitation and mystical symbolism in favour of an intellectual form language. The Gothic Age renounced the recondite and the hieratic to pursue dream images of a limitless universe. The Baroque painters renounced luxury, nerve excitement and rapidly changing fashions to achieve visceral emotive dynamism. The Neoclassic Age renounced the excesses of the Rococo, and promulgated a return to simplicity and symmetry.

Each classical age abjured subjectivity, pretention, materialism and over-civilization, ultimately returning to what J. J. Winckelmann has called the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” of the Greek aesthetic.

The current conceptual art market has been characterized as calcified, dispassionate, self reverential, inexplicable and unintelligible. Driven by an insatiable appetite for the artificial, the unique and the thrilling, it thrives in a delusory present tense of moral isolation and intellectual malaise.

It lives to burn the dead, taking down forms that have become inorganic and inconsequent, but ultimately fails to replace them with other forms that are pure, expressive and truly meaningful to anyone other than a charmed circle of connoisseurs… Qualis artifex pereo.

At significant risk here is the continuing health of “narrative”, that is, our universal sense of purpose. We need pure and natural forms to provide us with moral context, or, as Vaclav Havel observed, with a sense of “transcendental responsibility, archetypical wisdom, good taste, courage, compassion, and faith.”

*

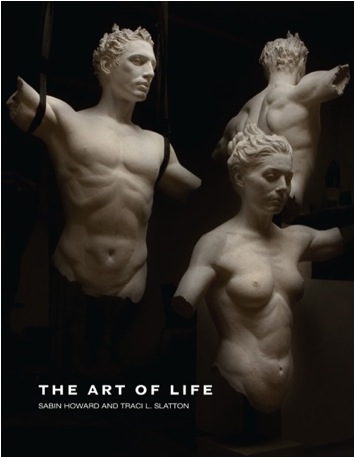

Sabin Howard, a contemporary American Neoclassical sculptor, appreciates the necessity to preserve and fructify the consequential narrative of our human aspirations. “I’m not trying to recreate the past,” he says, “I’m trying to take the past and apply it to the present.”

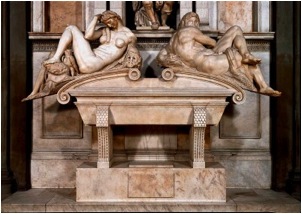

MICHELANGELO- Night and Day

It was a journey that began when he was fourteen years old and visited the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence. In the Medici Chapel he viewed Michelangelo’s penseriosi sculptures of Night and Day, and Dawn and Dusk on the tombs of Lorenzo and Giuliano de Medici. He was overwhelmed by the straining, twisting male figures of Day and Dusk, frustrated and locked within themselves, powerfully embodying wrath and pain. He was equally affected by the mysterious females of Night and Dawn– Night, drawn up, tense and unrelaxed against the motivated patterns of sleep; and Dawn, wearily resigned to being woken from it. They recall figures out of antiquity, and present as allegories shown to be living forms. It was an epiphany for Sabin, the first time he realized that he wanted to be a sculptor and “make timeless work that could be appreciated on many levels.”

His artistic path commenced at the Philadelphia College of Art where he studied with Walter and Martha Erlebacher, artists frustrated with abstraction and conceptualism, who had returned to classical figural representation. Walter taught a curriculum of “proportions. structure and translation of movement that came directly from the Renaissance”. After the Erlebachers, Sabin apprenticed with Paolo Carosone in Rome, where he came to appreciate the principles of design, surface fluidity, and the Roman system of luminosity, “where forms were flipped up to catch more light, especially around the eyes and mouth.” He concluded his studies at the New York Academy of Art, specializing in the structure of the figure, learning how to divide the body in terms of its masses, and how to group smaller parts within larger ones. These studies “deepened his understanding of the hierarchy of importance of parts to the whole and how parts move in relation to one another”.

*

Howard understands that the current art market, and sculpture-like activities in particular, appear to be driven by an abstruse power of conceptual expression. Dialectics, dissemination and deconstruction routinely obscure function, sense limits, and even the abstract qualities of design; overshadow them in favour of an intellectual probing of space.

He renounces this intellectual interference by advancing the timeless concept that clarity of design, expressed through anatomy and gesture, can be welded to a humanness which embodies the significance of life. This juxtaposition will place the represented figure in a space deeply invested with intense vitality and fuller meaning. “When you look at a figure,” Sabin says, “the pose, the morphology-all that dictates a narrative about an individual psychology.”

He is fascinated with the variation in body types: “There is an internal pressure within each body that pushes outward in a convex fashion. This is nothing less than life force energy which manifests the individual’s unique spirit and soul through body type and demeanor. No two people manifest this energy in the same way, and this uniqueness can be found in each body part, and in how the parts all fit together.”

Classical sculptural representation begins with an intelligible pose, a full 3 d realization- veristic, with no two points of view alike, yet ‘readable’ from any viewing angle. Organically asymmetrical, it has an expressive contour which can be observed, and clearly understood, from any point in space. Foreshortening should be seen as such, the silhouette should be characteristic of the body parts, and the expressive contours should appear in harmonious succession passing into every plane. Torsion turns literally on a progressive rotation of the horizontal axes of the human body.

Sabin Howard has followed this true classical approach to rendering the whole essence of a living phenomenon, eyes constantly on the past as well as the future, living in the consciousness of becoming.

HERMES

In HERMES, for example, he says, “My goal was to come up with a pose that invited viewers to move around it. I wanted a tremendous amount of energy, but I didn’t want it to be weighed down. So, I came up with a spiral pose where the arms were outstretched. By extending the arms and elongating the limbs and torso, I gave Hermes a more lyrical feel.”

“Everything in this sculpture is designed on a spiral system, the whole pose, to each of the smaller parts and how they fit into the larger parts. In most of my sculptures you have two things going on at once. You have a stable or an anchored leg representing the stationary, a fixed anchor system. Off that core or axis is developed a spiral, moving system. I place all my figures on a square base so that you can relate the pelvis and the rib cage and the head to the base. If you move up, the pelvis rotates clockwise, the rib cage rotates more clockwise; the head rotates even more, until you have the gaze that goes off in another direction.”

In this way visual limits are defined by the reference points of planes and patterns, and the representational content becomes expressive, charged with heightened emotion. A correct application of the modelling line, one based on a simultaneous relation of all the parts, ensures that we apprehend the statue directly in its depth and spatial extension, what Polykleitos referred to as “exact commensurability”.

The patterns and planes of composition in each of his sculptures reflect a rhythmic proportioning of limbs and the harmonious build of muscles. Sabin considers himself an architect working with human form. “The architectural part of the figure is the skeleton, or the structure. The organic part is the muscles, which always spin from one side of the pedestal to the other side of the pedestal, creating a spiral motion.”

“This is why Michelangelo’s work is so powerful.” he continues, “Because you have a connection between structure and architecture and movement. You have something that is solid, at the same time it has tremendous vitality and movement.”

“There is an internal pressure within each body that pushes outward in a convex fashion. This is nothing less than life force energy, which manifests the individual’s unique spirit and soul through body type and demeanour. No two people manifest this energy in the same way, and this uniqueness can be found in each body part, and in how the parts fit together. Using my knowledge of anatomy, I re-create this play of pressures in a sculpture, which therefore carries the presence of a unique being.”

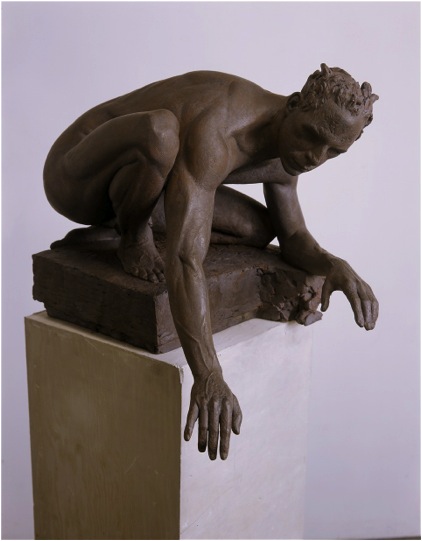

PERSISTENCE

As he completes the ordering of the body parts for each sculpture he permits enlargements and reductions in scale to accommodate metaphysical expression of form. “I take a tremendous amount of liberty with proportions. Many times I elongate parts or make other parts of the body thicker and more compact. These distortions are not accidents. With them, I can increase the psychological impact of the figure.”

To strengthen this psychological impact Sabin introduces a significant representational element, one which allows him to heighten the emotional content without resorting to intellectual meddling, or an unnecessary appeal to sympathetic understanding. Each element reflects knowledge of open and closed energy systems- the dynamic ordering of parts and processes as they stand in mutual interaction.

In the works illustrated in this survey, APOLLO, the sun god who brings light healing and expansion to the world, “has been carefully designed to fulfill this heroic task” (HOWARD /SLATTON). “His sternum is pitched toward the sky and it is the furthest point projecting out as he moves forward. That breast bone point is the brightest part of the sculpture. Everything else moves back and down, away from the light; he radiates from his heart. His chest is fully expanded, lifting skyward and moving forward. Apollo is all about luminosity. His outstretched palm catches the energy and light from the heavens; he shines the light on earth with his other hand. He leans forward dramatically, bespeaking his dynamic action and purpose.”

HERMES, an heroic scale figure, the messenger of Zeus, has been posed to project “self assurance and supreme self-containment”, stationary yet intrinsically rhythmical; balanced and intensely chiastic. PERSISTENCE presents as a figure compressed, “the weight and resistance of a body pressing in on itself: downcast eyes, thick brows and sinus cavities accentuated for anger, sternums directed toward the ground.” ARMOR, a departure for Sabin from his standing figures, crouches, compressed downward, yet reaching forward in anticipation. It is a figure of true ambivalent asymmetry.

ARMOR “rotates around the axis of his spine, so that one side of him is compressed and folded up…while the other side shows power building, ready to spring up explosively…On the archetypal level, this is certainly a Narcissus figure, trapped and mesmerized by his own reflection. He cannot see beyond himself. This is a modern concept that, despite its ancient mythological roots, aligns itself with modern man’s vision of himself as operating alone and inside himself in the universe”. (HOWARD/SLATTON)

ARMOR

ARMOR

The animate and animating forces are achieved by a proper employment of pure forms, not by intellectual interference. Howard refuses to transcend sense limits in favour of intellectualized space, advancing the restrained magnitude of the Apollonian soul- beauty of expression, against the overweening intellectualism of the Conceptual mechanism- power of expression.

*

Fifth century BC Greek sculpture, essentially Euclidian and point formed, saw the empirical visible body as the functional expression of a new way of being. “Soul in the last analysis, was the form of his body.” (ARISTOTLE)

The Neoclassic Age viewed “the measure of a narrative’s ‘truth’ in its consequences- (those which provided) a sense of hope, ideals, personal identity, a basis for moral conduct, explanation of that which cannot be known.” (POSTMAN)

Sabin Howard has absorbed the tenets of classical expression and has moved the tradition forward, presenting a contemporary “narrative” which is both functional and consequential.

He assumes constancy in each of his works through proportion and rhythm, using linear equivalents and simultaneous relation to conjure up his objective illusions.

He has taken the expressive forms of his art, transformed the variability of the constituent parts, rendered them intelligible and meaningful, and sculpts man, “not as he is, but as he aspires to be.”

While Nature may never show an underlying type, “but only the thousand and one individual variations of it” (CARPENTER) Sabin Howard has distilled the essence of contemporary man and continues to exhaust the significance of his being; each new sculpture offers understanding sufficient for each one, and for a time.

Quotes, unless identified otherwise, are compiled from conversations with the sculptor, and from articles published in American Arts Quarterly, American Artist Magazine and Fine Art Connoisseur, and the sculptor’s own book, “The Art of Life”.

All other citations available upon request.

Related Reading: Carpenter, op cit. Spengler, op cit.

Postman, Neil “Building a Bridge to the Eighteenth Century” (1999)

SABIN HOWARD, TRACI L. SLATTON- THE ART OF LIFE Parvati Press 2012

Contact: parvatipress.com

PANEM ET CIRSENSES

“It’s, like, if a tree falls down on your land, or in your street, it looks…bigger. You drive to work every day, everything’s the same, you know where you are. Then one day you drive to work, and a tree’s fallen down, and you go ‘Fuckin’ hell!’ You look at the tree and it’s massive. You never notice it until it falls down. Artists do that!” Damien Hirst- Contemporary British conceptual sculptor

NEOCLASSICAL WHO’S WHO- CANADA

Dynamic Symmetry- Jay Hambidge (1867-1924)

On November 16 1917 George Bellows wrote to fellow American artist Robert Henri:

“A new star has risen in the field of art analysis. Jay Hambidge …comes forth as John the Baptist proclaiming the coming of a new understanding and the key to Greek mysteries. I am attending a little class of his once a week and think we’re on the trail of something which may be worthwhile.”

Eclipsed in art history by the aesthetic and commercial upheaval resulting from the Amory Show of 1913, the design theories of Canadian artist Jay Hambidge, although controversial and influential in their day, have been ignored in the latter part of the century. They do not appear to fit in with the sensibilities of the modern movement. Contemporary art, with a casual disregard for limits, appears to consider design as purely instinctual. However, with the resurgence of interest in design as a rational process by graduates of the new atelier systems, Hambidge’s theories, as well as those of other early 20th century art theorists such as Samuel Colman, Hardesty Maratta, and Denman Ross may have an increased relevance for contemporary Neoclassical art.

Hambidge perceived that in the symmetrical forms of nature (ex.-the centre of a sunflower, or the chambered shell of a nautilus) there is a certain principle of proportion which is constant and may be expressed mathematically. He believed as well that the ancient Greeks had this knowledge and used it to design their architecture, sculpture and ceramics.

Dynamic (versus static) symmetry obtains regularity, balance and proportion in design by using a contiguous series of diagonals and reciprocals to the rectangular areas, rather than the plane figures of geometry or measurements of length units. These ‘whirling’ rectangles animate the compositional elements, allowing the artist to place the subject harmoniously and dynamically within a structured, commensurable framework.

The technical aspects of Dynamic Symmetry are beyond the scope of this journal. The mathematical formulae necessary to understand them are mind numbing, and the exactness of Hambidge’s math was questioned even in his day. However, all things being equal, “the specifics of the mathematics (matter) less than the system of generating proportionate areas and using geometry to bring a rational rigor to composition” (FRANK).

Having command of a natural design methodology ultimately allows the artist to achieve an equitable balance of variety in unity, especially in large format compositions. And, contrary to the presumption that any ‘golden section’ geometric formula inhibits the free spirit in art, the underlying truth is that technical understanding, while no short cut to creativity and certainly no substitute for thinking, works to strengthen the imagination and power of expression. As Bellows rightly observed, “if a thing is made easier by technical understanding then…your strength is conserved for those things that yet remain troublesome.”

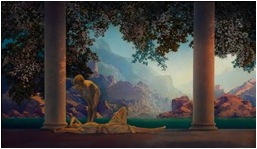

Maxfield Parrish- “DAYBREAK”

The disciples of Dynamic Symmetry include some of the most well regarded artists of the early 20th century. Emil Bistram, George Bellows, Robert Henri, Maxfield Parrish, and Edward Weston all used some variation of it in their work.

Reference: FRANK, Marie Ann- “Denman Ross and American Design Theory”- esp. Chapter 4- “Geometry, Pure Design, and Dynamic Symmetry”

THE DISCERNING COLLECTOR Volume 1 Number 2

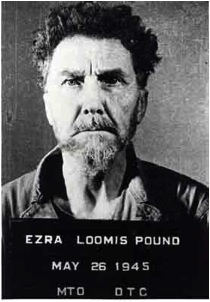

Ezra Pound, American poet and walking contradiction, once observed:

“Artists are the antennae of the race but the bulletheaded many will never learn to trust their great artists” (“Instigations of Ezra Pound”1967)

Photo of Pound taken at the Army Disciplinary Training Centre (Source-Wikipedia)

Regardless of how you feel about Pound, (my favourite is Macha Rosenthals’s observation that in Pound “…all the beautiful vitality and all the brilliant rottenness of our heritage…were both at once made manifest”) it may prove helpful and instructive to have a look at his essay of 1913 “The Serious Artist” for a few basic principles relating to discernment in collecting.

*

(All quotes are from the essay)

It is through the arts, whose proper subject is the study of mankind, that we are able to obtain significant data regarding the nature of man considered as a “thinking and sentient creature”. The ethical data collected will give us an indication of what man desires, and what is compatible with his physical wellbeing, his inner nature and his condition.

The ethical data, observed through ‘soft science’ (i.e. science that relies on conjecture and qualitative analysis rather than rigorous experimentation) will allow us, first and foremost, to differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art, and understand the inherent immorality of the latter.

‘”Bad art” Pound states, “Is inaccurate art. It is art that makes false reports.”

False reports about the nature of man, the artist’s own nature, the nature of his ideal of the perfect, the nature of God, the nature of the life force, the nature of good and evil, and the degree to which the artist suffers or is made glad.

If the artist falsifies his reports on these matters to “conform to the taste of his time… or to the conveniences of a preconceived code of ethics, then that artist lies. If he lies out of deliberate will to lie, if he lies out of carelessness, out of laziness, out of cowardice, out of any sort of negligence whatsoever, he nevertheless lies.”

Pound carries it a step further. It takes “a great deal of talking to convince a layman that bad art is ‘immoral’. And that good art however ‘immoral’ it is, is wholly a thing of virtue. Purely and simply that good art can not be immoral. By good art I mean art that bears true witness, I mean the art that is most precise.”

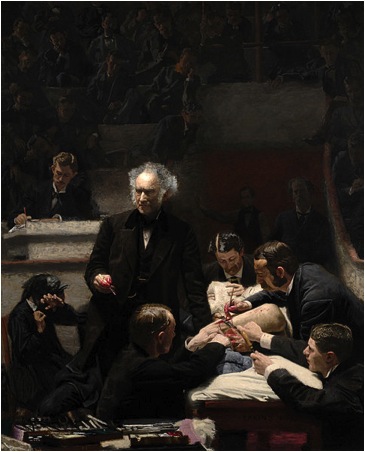

Thomas EAKINS “The Gross Clinic”

In medicine there exists an art of diagnosis and an art of cure. The same exists in the plastic arts. One is called ‘the cult of ugliness”, the other “the cult of beauty”. The cult of ugliness is diagnosis-“surgery, insertions and amputations”. The cult of beauty is cure- “sun, air and the sea and the rain…”

“Beauty in art reminds one what is worthwhile. I am not now speaking of shams. I mean beauty, not slither, not sentimentalizing about beauty, not telling people that beauty is the proper and respectable thing”. Beauty is…”.an April wind…a swift moving thought in Plato…a fine line in a statue”.

Diagnosis and the cult of ugliness “remind one that certain things are not worthwhile. It draws one to consider time wasted”.

They can co-exist: “The cult of beauty and the delineation of ugliness are not in mutual opposition”.

The artistcan become a social ‘scientist’, giving us a permanent property based on ethical data which is used to determine what sort of creature man is. A ‘scientist’, who “presents the image of his own desire, hate or indifference. The more precise his record the more unassailable his work of art.”

“The touchstone of an art is its precision. The precision is of various and complicated sorts and only the specialist can determine whether certain works of art possess certain sorts of precision. I don`t mean to say that any intelligent personcannot have more or less sound judgement as to whether a certain work of art is good or not. An intelligent person can usually tell whether or not a person is in good health…it takes a skillful physician to make…diagnoses or to discern the lurking disease beneath the appearance of vigour.”

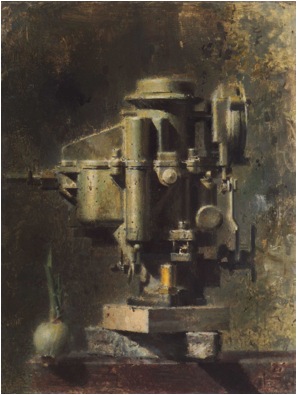

Walter Tandy MURCH “Carburetor”

The discerning collector, an intelligent layman who aspires to specialist knowledge, will not seek out art he/she doesn`t like, nor come to conclusions about content in art based on ‘say so’, nor have a closed mind about varieties of diagnosis and cure. The collector should be able to come to a specialist’s opinion as to what art is good through his own initiative, applying specific principles of discernment to support his judgement, remembering that it is not the artist’s place to ask you to learn, nor to defend his particular works of art.

The collector should be able to recognize artwork in which the artist is perfectly controlled, saying exactly what he means, with complete clarity and simplicity, using technique which allows him to do exactly what he set out to do, and always aware that “the most efficient way to keep quiet is to say nothing…”

PANEM ET CIRSENSES

Blog note: Altogether too many emerging Classical/ Realist Artists cite ‘influences’ from Rembrandt to Sargent to Sorolla, trumpeting their devotion to “Beauty” and the Classical tradition as a means to establish pedigree for artwork that often is predictable, formulaic and lacking in depth.

In more ways than one…

“Who carried the calf may carry the bull”- (cited in Petronius Arbiter- Satyricon”)

(FELLINI- Satyricon)

And, not to put too fine a point on it…

“There is a very present danger of confusing Origin and Validity, and of imagining that because we have discovered how the various conventions and devices arose we have therefore fully explained and understood them.”

CARPENTER, Rhys- “The Esthetic Basis of Greek Art”

CLASSICAL WHO’S WHO PLATO

Although other great ancient civilizations espoused ‘theories’ of art, the Western civilization owes its most significant critical debt to the ancient Greeks. The Greek word “aisthetikos (sensitive, sentient) gave us ‘aesthetics’, which is our word for the critical study of art and culture.

Aesthetics proceed from philosophical speculations about art and beauty, the earliest discussions of which are contained in the dialogues of PLATO. While Plato does not bring forward a defined theory of aesthetics (as is present in Aristotle), there are elements in the dialogues which begin the process of definition.

Plato treats art and beauty almost as if they were opposites, art a great danger, and beauty, the greatest good.

The danger of art lies inherently in the areas of imitation (mimesis) and inspiration. Because art originates in appearances rather than reality, there is a danger that the soul will be directed toward the artificiality of these appearances rather than proper objects of enquiry, such as true knowledge. As well an artist may require divine intervention (sitting “on the Muse’s tripod”) to bring value to his imitative efforts, value which may not be there otherwise.

Beauty, by comparison, originates in the realm of intelligible objects. There is a form to ‘Beauty’ which engages the soul, allowing sensory experience to progress to philosophical deliberation, and to thoughts of Absolute Beauty.

Plato determines the worth of art less by its formal qualities, than by how it shapes moral attitudes through the search for mystery and universal truths

A more detailed discussion of Plato’s aesthetics can be found in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (www.) , from which this entry has been compiled.

Dino VALLS “CAERULA” 2005

SOME PRINCIPLES FOR DISCERNMENT IN COLLECTING ART

“Know then thyself, presume not God to scan

The proper study of mankind is man” Alexander POPE

As you look to form a specialist’s opinion, to see beyond the mere external dimensions of contemporary neoclassical art and probe its deeper meaning, the following principles should help to further your understanding:

- COMMUNITY- Art is a thread in the fabric of Life. Artistic sensibilities should always be informed by observed ethical data, allowing the artist to judge the unknown by the known, and the uncertain by the certain, recognize an enduring moral order in complexity and chaos….and have courage in his/her convictions. Truth should never be purely subjective.

Juliette Aristides “Jeremy” - PERMANENCE AND PROGRESSION- Art should be faithful to its organic development. It should temper the stability and continuity of technical knowledge with the intuitive understanding that prudent change and reform prevent stagnation. To paraphrase Coleridge- Art can never be too cultivated,but easily may become over civilized.

- DESIRE- Art should allow both artist and audience to see Destiny clearly. A strong desire to understand why art is necessary, and a consuming passion to know the truth, should be shared by both parties. Thereafter it becomes a matter of thesis, antithesis, and pattern. Understanding “Who owns my eyes”, “Do I trust my heart”, and “Do I believe in the beauty of my dreams” will help both parties determine motive over issue, maturity over intent, clarity over comfortable confusion. Each then will see the chain of Destiny, as Winston Churchill counselled, “one link at a time”.

Carolyn PYFROM- “now we see through a glass darkly” 2005 - PRESCRIPTIVE WISDOM-A sundial in the shade??- The depth of validity for artistic sensibility would appear to turn on how the artist best uses talent and skill- and whether he/she understands the true spirit of gift giving. Talent is a combination of genetics and environment, and skill the result of hard work. But the willingness to bear true witness, to open the depths of one’s soul to scrutiny under a blazing sun, and to offer something other than simple remedies for the ills of a complex society, is the enduring gift and determinate necessity that art can provide. To whom much is given…much will be required.

- SERENITY- the sensuous instant. Neoclassic art, both traditional and contemporary has embraced images of the nude human form in a variety of uses- symbolic, heroic, esoteric, erotic….The debate of “naked vs nude- moral vs immoral” has raged for years without apparent resolution. However, as Pound observes, good art cannot be immoral when it is precise, that is, when it bears true witness to the human condition, and represents a deep moral principle or the purest precepts of intuitive reasoning.

Angela CUNNINGHAM- “Maria” - ORIGIN AND VALIDITY- Conformity to Tradition- the pure present- T S Eliot says it best: ”The emotion of art is impersonal. And the poet cannot reach this impersonality without surrendering himself wholly to the work to be done. And he is not likely to know what is to be done unless he lives in what is not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he is conscious, not of what is dead, but what is already living.” (Tradition and the Individual Talent)

A SCANNING GOD- “Writing Straight on Crooked Lines”

“They say God writes straight on crooked lines, but I suspect that these are exactly the lines He prefers, first to show His divine virtuosity and conjuring skills and second because there are no others. All human lines are crooked, everything is a labyrinth. But the straight line is not so much an aspiration as a possibility. The labyrinth itself contains a straight line, broken and interrupted, I concede, but permanent and expectant.” JOSE SARAMAGO- “Manual of Painting and Calligraphy” 1977

NEOCLASSICAL WHO’S WHO- IRELAND

JAMES BARRY -EDMUND BURKE

Continuing the thought that the cult of beauty and the delineation of ugliness may not be in mutual opposition, it is interesting to look at a precedent of opposites coexisting as means to a specific end. This situation is present in the stylistic adjustments made by the Irish Neoclassical artist James BARRY (1741-1806) to his later work to reflect the philosophical principles of his friend Edmund BURKE (1729-1797).

Burke’s early treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) promotes a clear division between two types of aesthetic sensation: the ‘beautiful’- founded on pleasure, and the ‘sublime’- something awesome and terrifying, and generally related to pain.

Burke essayed that the objects which give rise to these sensations have distinct physical properties. Beautiful objects are comparatively small, have smooth contours, are gently undulating, and continually flowing with a hardly perceptible beginning, end or interruption. They should not be obscured but exist in an even natural light.

Sublime objects are vast in dimensions, solid and massive. Straight lines and angular accents predominate. Such objects should be wrapped in gloom, or seen in sudden intense illumination (ex-lightning).

James BARRY “King Lear Weeping over the Body of Cordelia” 1786-88 The Tate

In “King Lear” the ‘sublime’ or painful dominates the forward picture plane (the image is a horrifying one- the death of all one’s children). The light source from above is glaring and harsh, and delineates the main characters- Lear with Cordelia in his arms, and Goneril and Regan on the ground. A body, presumed to be Edmund, is being carried off left. The figures are crowded forward, surrounded by shadows and a pervasive sense of gloom. Straight angular axis points confine and separate the figures.

The ‘beautiful’ exists in the background. A Stonehenge like structure is directly above Cordelia’s head. Worshippers gather in congenial familiarity, figures reduced in scale and placed farther back in the picture plane. The path to the temple winds gently to the meeting place. Off in the background left is a tranquil harbour, again with reduced figures placed farther back. Each scene is illumined by natural light coming through the clouds.

In “Lear”, Barry moves easily from the sublime to the beautiful incorporating clearly recognizable stylistic elements, making “adjustments in his stylistic vocabulary when dealing with different types of subjects, and these adjustments are unequivocally related to contemporary thought concerning the inherent visual qualities of such subjects.”

Compiled from: R R WARK “A Note on James Barry and Edmund Burke”

Note:

The sensibilities present in Barry’s “King Lear” have been used to comparable effect in Contemporary Neoclassical Artist Patricia Watwood’s striking reimagining of the Pandora myth.

Patricia WATWOOD “Pandora” 2011

In “Pandora” the sublime or painful commands the forward picture plane. The image is the mythical Pandora who, although expressly forbidden to do so, has succumbed to her curiosity, opened a box, and let loose evil on the world. The figure is crowded forward in the plane, surrounded by the gloom, darkness and detritus produced by our civilization’s devotion to technology. Straight angular, almost knifelike axis points bisect and contain the soft edges of the figure. Illumined by a harsh light from above, Pandora appears to raise her hand, half in surprise at the results of her action, and half in defense against them.

The beautiful- a harsh but strangely compelling vista of nuclear power plants, multi denominational churches and sky scraping architecture exists in the background, lit by suffused light coming through the clouds. It a world of our making: ready power, unfettered freedom of speech, and deified commerce- one that we must make the best of.

Central to the composition is the image of the Eastern Bluebird, which Watwood has used to replace the Elpis or Hope figure in the original myth. The Elpis was the only item that remained after all the evils had been let loose. Once close to extinction, the Bluebird has made a resurgence in recent years, and symbolizes for Watwood “happiness, love and renewed hope”; in the same manner that the Stonehenge structure symbolized unification and peace for Barry in “Lear”. A further symbol of a seagull, traditionally considered by the Celts as the messenger bird from the heavens to mortals, flies across the river carrying the message of hope to a waiting world.

Patricia Watwood says that “Pandora” “arose from (a) stew of anxiety and dread” arising from a suspicion “that our current course is not sustainable-and that the house will fall on our heads”. Part of the message in the work deals with “the complex reasons for terrorism”. Watwood, by way of ‘diagnosis’, asks the question “How does my way of life (religion, culture, worldview) compare to that culture over there. Curiosity, Pandora’s natural inclination leads to clash of civilizations and ideologies. Sometimes we meet the foreign with delight and excitement, sometimes we meet it with abhorrence and fear.” The result of our “curiosity” may well be incidents like September 11, 2001. By way of ‘cure’, Watwood offers that “No matter how dire, how untenable, how impossible the situation at hand may seem, there is always hope, which gives us strength and guidance to keep going”.

Quotations are taken from the artist’s writings on the internet blog- artistdaily.com 6 July 2011

THE DISTINCTION OF VALUE AND THE VALUE OF DISTINCTION

*

A number of years ago John Morra, a contemporary realist painter very attuned to the present moment of the past, recommended that I read the work of Neil Postman, media theorist and cultural critic.

Postman’s books from “Amusing Ourselves To Death” (1985) to “Building a Bridge to the Eighteenth Century” (1999), deal with careful thinking, the need to probe beneath the surface of information, the dangers of statistics, and above all, the dearth of serious ideas in our new world order. Each work is informed, in the main, by a contemporary humanism that favours morality over science, and purpose over politics and economics.

Recently I had occasion to re-read his 1992 work “Technopoly”.

John MORRA “ Mertz”

John MORRA “ Mertz”

*

Addressing specifically the trends and relationships of contemporary American civilization, Postman presents our current social situation as “Technopoly”- “a twentieth-century thought-world that functions not only without a transcendent narrative to provide moral underpinnings but also lacking strong social institutions to control the flood of information produced by technology.”

It is a milieu in which each member believes that “society is best served when human beings are placed at the disposal of their techniques and technology.” An attitude prevails “that there is nothing worth preserving that it should stand in the way of technical innovation.” The tie between information and human purpose is severed; and politics, science and economics are routinely placed ahead of morality.

Apparently incapable of appreciating that responsibility is something other than fealty to country, corporation and success, members of a Technopoly justify “commodity capitalism” by trumpeting the achievements of unrestrained innovation and technical efficiency. Twentieth century technology is so adept at providing them with “convenience, comfort, speed, hygiene, and abundance, that there (seems) to be no reason to look for any other sources of fulfillment or creativity or purpose”.

Physical and natural science become the authority in all things. The methods of natural science- measurement by quantitative data and use of deterministic models, can be applied to the study of human behaviour. Specific principles of social science can be used to organize society on a rationale and ‘humane’ basis (i.e.-ones designed to control human behaviour and set it on a proper course- subtly at odds it would appear with the humane principles of liberal democracy espoused in the 18th century.) Faith in science can serve as a comprehensive belief system that gives meaning to life as well as a sense of well being, and morality.

Precise knowledge, buttressed by objective facts and testable theories is preferred to truthful knowledge, built on a tradition of metaphysical logic, spiritual belief, and knowing what is beyond belief.

Tradition is placed on the sacrificial altar of technological efficiency and prosperity. Human judgement is considered lax, ambiguous and unnecessarily complex; it is made irrelevant and then invisible. With tradition eradicated, the authority of Technopoly can now redefine “what we mean by religion, by art, by family, by politics, by history, by truth, by privacy, by intelligence so that our definitions fit its new requirements.”

Information is the supreme tool of Technopoly- written, oral, image, television, computers, polls, entertainment, silicon chips, IQ tests, message, medium-a tidal wave of content, sometimes dazzling but often without substance.

It is a new type of information, one that separates moral and intellectual value, rejects the necessity of interconnectedness, proceeds without context, argues against historical continuity, and offers fascination in place of complexity and coherence. Quality and utility are displaced by quantity, distance, and above all-speed of dissemination.

Technopoly provides enlightenment for moral and intellectual relativists, the former ”incapable of providing right thought and proper behaviour”, the latter “refusing to defend their own culture and no longer committed to preserving and transmitting the best that has been thought and said.”

Joseph BEUYS La Rivoluzione siamo noi 1972

Photograph by Giancarlo Pacaldi

Controls which should be in place to limit the deleterious effects of indiscriminate or contradictory information have been revised as well.

Members of Technopoly manage information by using statistics, information polls, IQ tests and so on, believing that information can be stored and measured scientifically. They believe, for example, that IQ scores are our intelligence, and that opinion polls are what everyone else believes, “as if our beliefs can be encapsulated in such sentences as ‘I approve’ and ‘I disapprove’.

Traditional information filters, such as religion, education, politics and family no longer operate with real effect, and we turn increasingly to bureaucrats, experts, and social scientists to provide direction in the development of a new social order. Aided by computers and similar broadcast technologies, ‘experts’ now control the flood of data. Technical solutions, originally intended for mechanical situations are used now for human problems, finding their way into social, psychological and moral affairs.

Casey BAUGH “Static”

*

The foregoing has been compiled from selected chapters in ”Technopoly” , ones that I felt would be helpful for collectors of contemporary Neoclassical art. Quotations are from the text (or otherwise noted). I do recommend however, that the book be read in its entirety. It is eminently readable, logically presented and supported by appropriate references. Not the jeremiad that some readers have made it out to be, “Technopoly” still has relevance today. Although biased toward traditional humanism, it identifies aspects of Technopoly which have proven to beneficial to our culture, but warns that we must understand and control them as tools and technologies, and place them in the context of our larger human goals and social values.

*

In “Technopoly” Postman provides a very succinct and serviceable overview of the relationship between tradition and symbols. I quote:

“There can, of course, be no functioning sense of tradition without a measure of respect for symbols. Tradition is, in fact, nothing but the acknowledgement of the authority of symbols and the relevance of the narratives that gave birth to them. With the erosion of symbols there follows a loss of narrative, which is one of the most debilitating consequences of Technopoly’s power.”

Narratives are “a story of human history that gives meaning to the past, explains the present, and provides guidance for the future. It is a story whose principles help a culture to organize its institutions, to develop ideals, and find authority for its actions.”

Collectors will find the precepts contained in Postman’s summary chapter- “The Loving Resistance Fighter”, helpful as they view and appreciate contemporary Neoclassical artwork which runs contrary to the conceptual, experimental, provisional, and commodified contemporary art processes that are ubiquitous in Technopoly.

Contemporary neoclassical art should connect with those levels of feeling that are not expressive in discursive language, and should

- Refuse to accept efficiency as the pre-eminent goal of human relations

- Free itself from belief in the magical powers of numbers, and not regard calculation as an adequate substitute for judgment, nor precision as a synonym for truth

- Stand as suspicious of the idea of progress, and not confuse information with understanding

- Take the great narratives of religion seriously and not believe that science is the only system of thought capable of producing truth

- Appreciate the difference between the sacred and the profane, and not ‘wink’ at tradition for modernity’s sake

- Admire technical ingenuity but not think that it represents the highest possible form of human achievement.

Casey BAUGH “Illuminations”

Casey BAUGH “Illuminations”

PANEM ET CIRSENSES

“Part of the challenge I see in trying to focus attention away from market-oriented art is figuring out how art that behaves like a commodity can be counteracted by artists. One way to do this is to create communities. Another way-and I think this is very very important-is to create anti-market polemics”

Irving SANDLER

CREATION, COLLECTING, CONTINUITY

*

THE SENSE AT ONCE OF THE PAST AND THE PRESENT

“Unlike technology, art does not progress; there is no supersession of the old by the new. Every great work of art from the past is capable of a rebirth, of a renaissance, and so when we survey great areas of history we become aware of a polyphony of influences, a choir of many voices.”

NIELS VON HOLST

While art may not progress, it does have the ability to depict images of experiences which contain, as Goethe observed, “the sense at once of the past and the present”.

The essence of an historical event can be rendered wholly contemporary if reinterpreted in context by a person who, quite simply, is able to separate event from recurrent process; one who is willing to show unique happenings from a spinning world of silence, work and suffering.

Using a free act of will, the contemporary neoclassical artist should see that uniqueness can never be part of a process, that continuity is a matter of influence and reinterpretation, (rather than a process of association, selection and effect), and that certain needs and aspirations exist, shared unknowingly by all men, which are essential to civilized living. The work of this artist should name names- regardless of consequence; designate what truly is worthwhile- without concern for censure or profit; and finally, help the viewer to understand that there are happenings in this world that exceed our ability to explain them. Relived and remembered, the past becomes present, and both artist and viewer share a unique understanding of time. The art of our age can find its own place. Creative power will become a ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ to transcend process, and uncover identity and ideology through beauty and metaphysical truth.

Zoey FRANK “Homesteader” 2011

*

Historicism, manifested as a sympathetic understanding for the art of the past, may be the distinctive hallmark of a productive culture. It begins as a mimetic dialogue, in which the images and motifs of historical events become assimilated, adapted, revised and reworked to satisfy specific moral, social and cultural imperatives. The acculturation continues, progressing to imitation which can be rendered either exactly as a copy, individually as an interpretation, or through a synthesis of numerous antecedents. The conversation concludes with the production of artwork which, although an amalgam of influences- “a choir of many voices”, stands as the unique expression of a particular environment and ideology.

Teresa OAXACA “Patrick”

*

The grandeur of Rome from the glory that was Greece.

As Rome grew in power from 300 BC onward, the number of artworks brought to the city, usually by way of military triumphs, grew correspondingly, often reaching staggering numbers. In 180 BC Fulvius Nobilior, after his conquest of the Aetolian League, included 785 bronze and 230 marble statues in his triumphal procession.

The Romans, who previously were only faintly attracted to the Greek aesthetic and veneration for beauty, began to surround themselves increasingly with aspects of Hellenic culture. “The name of Hellas now began to imply the ultimate refinement of pleasure and the ability to derive enjoyment from a world of art whose roots lay more deeply embedded in the past than Rome.” (VON HOLST)

Outwardly, cultured Romans still subscribed to the ‘mos maiorum”- the customs of the ancestors, which included trustworthiness, dutiful respect, discipline, and self control among other virtues. But inwardly the need for social distinction, dignified status and intellectual prestige would lead them down avenues that were often at odds with ‘gloria’ and ‘memoria’.

Using wealth as a touchstone the ambitious Roman, who wished to appear cultured, would fill the private spaces of his home with fine and decorative art objects, usually Greek in origin. The Emperor Tiberius paid 60,000 sesterces (relative modern equivalent- $1.2 million) for a painting by Zeuxis of the high priest of Cybele, and had it hung in his bedroom. And in Roman times, even as now, there were issues of ‘reach and grasp’. In a letter by Cicero written about 60 BC there appear the words “Jam sunt venales tabulae Tulli” (translation-“Tullius’ pictures are already up for sale”) (VON HOLST)

The collecting zeal for Hellenic art objects spread to cities outside of Rome. The excavations at Pompeii, a city near Naples buried by ash from the volcano Vesuvius in AD 79, yielded a sensational treasure of both authentic Greek statues and ‘archaicized’ imitations.

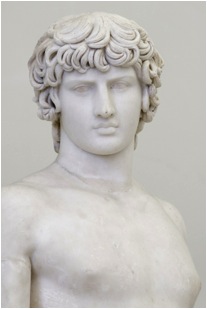

The Hellenization of Rome reached its zenith during the time of Hadrian (76AD-138AD), whose love of 5th century Classical beauty was crystallized in the concept of ‘life imitating art’. The Emperor’s special friend Antinous, a young Greek man very much to type, met an untimely death in the Nile. Hadrian, inconsolable, made him a god not long after his demise. Cities were named after Antinous, medals struck in his image, and cult statues in the archaic style were commissioned for shrines and temples.

Antinous Farnese

*

All organic things are composed of a beginning, a middle, and an end. The Roman absorption with Classical Greek culture, which began in 300 BC, and reached its apogee in 150AD, concluded around 350 AD. “In the last phase of antiquity there (was) a falling off in the development of art. Weary of liberty, men took refuge in new self-imposed constraints. Earthly things lost their value.” (VON HOLST)

In 350 AD the Emperor Constantine transferred the seat of Roman power to Byzantium (now Constantinople). Deliberate primitivism in art replaced the Classical ideal of harmony between body and spirit. The Barbarians, quite literally, were at the gate. Rome was sacked by Alaric and the Visigoths in 410 AD. It was a very long way to the Abbot Suger.

*

J J Winkelmann wrote “Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture” in 1750. The publication of this book is considered the starting point of the Neoclassic movement, one which continues with strength to this day. Which Barbarian will be at our gate in 2300 AD??

Reference: “CREATORS, COLLECTORS, AND CONNOISSEURS- The Anatomy of Taste from Antiquity to the Present Day” NIELS VON HOLST

Edgardo Sambo (1822-1966) “Tre Modelli” Trieste

*

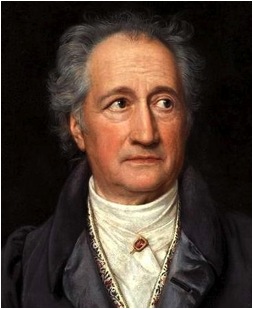

“Aye”, said Goethe, “What can be more important than the subject, and what is all the science of art without it? All talent is wasted if the subject is unsuitable. It is because modern artists have no worthy subjects, that people are so hampered in all the art of modern times. From this cause we all suffer. I myself have not been able to renounce my modernness. Very few artists are clear on this point, or know what will really be satisfactory.”

Conversations of GOETHE

Portrait of Goethe- Joseph Karl Steiler 1781-1858- Alte Pinothek

*

A SCANNING GOD

“One cannot remain immobile where the political and aesthetic customs and potentialities are so conspicuous and compelling: one must take another step.” Letter- Boris PASTERNAK to Kurt WOLFF

“I must…take this further step and go beyond my limitations and the limitations of thought, art, and religion of our time. And this requires effort and suffering. I simply cannot sit down and accept my limitations…But I must take care most of all not to be conte nt with merely fanciful transcendence- going beyond my limitations in thought and imagination only. It must be a real transcendence.”

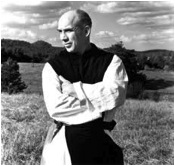

Thomas MERTON

Thomas Merton in the fields near the Abbey of Gethsemani

(Credit: Sybille Akers)

“People of our time are losing the power of celebration. Instead of celebrating we seek to be amused or entertained. Celebration is an active state, an act of expressing reverence or appreciation. To be entertained is a passive state- it is to receive pleasure afforded by an amusing act or spectacle…Celebration is a confrontation, giving attention to the transcendent meaning of one’s actions.”

ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL

“The gods did not reveal from the beginning, all things to us; but in the course of time, through seeking, men find that which is better. But as for certain truth, no man has known it, nor will he know it; neither of the gods, nor yet of all the things of which I speak. And, even if by chance he were to utter the final truth, he would himself not know it; for it is but a woven web of guesses.”

XENOPHANES

Julio REYES “HEADWINDS”